Equipartition Theorem and Analytical Results for a Quartic Potential

In this post I will discuss the application of the equipartition theorem to a non-quadratic Hamiltonian.

The equipartition theorem states that, for a system in thermal equilibrium, the quadratic degrees of freedom of a Hamiltonian share the same mean energy value. This happens because a system in thermal equilibrium has energies distributed according to the Boltzmann distribution

\[P(E) \propto e^{-\beta E}\]For a quadratic Hamiltonian, the result is well known. Consider the potential term of a harmonic oscillator, for instance

\[U(x) = k x^2 / 2\]Then

\[\langle \beta U \rangle = \frac{1}{N_2} \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} \frac{\beta k x^2}{2} e^{-\beta k x^2 / 2} dx \ ,\]where $N_2$ is a normalization constant for the quadratic potential.

\[N_2 = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} e^{- \beta k x^2 / 2} dx\]The result is given by the Gaussian integral

\[\frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi \sigma^2}} \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} e^{-x^2 / 2 \sigma^2} dx = \sigma^2\]and we obtain

\[\langle \beta U \rangle = 1/2\]Now let’s consider the non-quadratic potential

\[U(x) = k_1 x^4 / 4 + k_2 x^2 / 2 \ ,\]where $k_1$ must be positive, but $k_2$ may be positive or negative.

The notation for this problem can be simplified if we use dimensionless variables. Here, all units can be measured in terms of $\beta$ and $k_1$. Then, $V = \beta U$ is a dimensionless energy and $z = (\beta k_1)^{1/4} x$ is a dimensionless length. The expectation value of $V$ will depend only on the dimensionless parameter $D = \sqrt{\beta / k_1} k_2$.

\[V(z) = z^4 / 4 + D z^2 / 2\]Another limit which can be calculated is that of $D = 0$, the purely quartic oscillator

\[\langle V|_{D=0} \rangle = \frac{1}{N_4} \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} V|_{D=0}(z) e^{-V|_{D=0}(z)} dz = 1/4\]This result is different from the classic equipartition theorem, known from textbooks. Notice as well that the normalization constant is different here!

But the mean value can be found analytically for arbitrary values of $D$. These are complicated integrals for which I found results using Mathematica. Let’s see what we obtain. First, if $D > 0$, the result is

\[\langle V \rangle = \frac{1}{N_+} \int V(z) e^{-V(z)} dz = \frac{1}{8} \left(2-d^2+\frac{d^2 K_{3/4}\left(\frac{d^2}{8} \right)}{K_{1/4}\left(\frac{d^2}{8}\right)}\right)\]The symbol $K_{\alpha}(x)$ is used for the modified Bessel function of the second kind.

This result has an horizontal asymptote, as $D\rightarrow\infty$, which is $\langle V \rangle = 1/2$. This corresponds to the quadratic limit, in which the $x^2$ part of the potential is infinitely more relevant than the quartic term. And the limit of $D\rightarrow0$, corresponding to the purely quartic potential, we obtain $\langle V \rangle = 1/4$, as expected.

Now, if $D < 0$:

\[\langle V \rangle = \frac{1}{N_-} \int V(z) e^{-V(z)} dz = -\frac{d^2 \left(I_{3/4}\left(\frac{d^2}{8}\right)+I_{5/4}\left (\frac{d^2}{8}\right)\right)+\left(d^2-2\right) I_{-1/4}\left(\frac{d^2}{8}\right)+\left(d^2+2\right) I_{1/4}\left(\frac{d^2}{8} \right)}{8 \left(I_{-1/4}\left(\frac{ d^2}{8}\right)+I_{1/4}\left(\frac{d^2}{8}\right)\right)}\]Here, the symbol $I_{\alpha}(x)$ is used for the modified Bessel function of the first kind.

This result has no horizontal asymptotes. Instead, its limits are $1/4$ as $D\rightarrow 0$, the same limit as for the positive $D$ case, and $-\infty$ for the limit $D\rightarrow-\infty$. This is also expected since the latter limit represents a potential proportional to $-x^2$, which has no minimum, hence all particles in the system fall to an energy of $-\infty$, and this is the mean value.

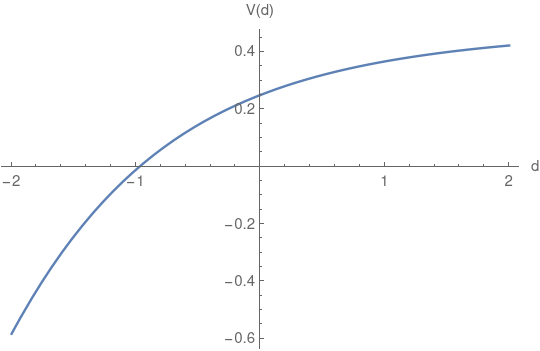

The curve we obtained analytically for $\langle V(D) \rangle$, visually, is shown in the figure:

Interestingly, this function seems continuous, even if it had to be split in two cases to be calculated. I calculated the numerical value of some derivatives and they give strong evidence that this function is indeed continous. The left and right limits of the derivatives at $D=0$ give the same values, up to the 6th order. But each derivative is much more complex than the last to calculate. The time it takes to evaluate them grows exponentially, so I stopped at order 6.

This is a simple example, but it’s always interesting to find results which can be carried out analytically.

The mathematica code used to find these results can be found on github.