Enumeration of Prime Parking Functions

Say $n$ cars need to park in $n$ spots, in a one-way street, but they have to announce beforehand in which spot they prefer to park. How many functions exist that allow every car to park? This is the problem of the parking functions, and I’ll discuss a way of efficiently enumerating them.

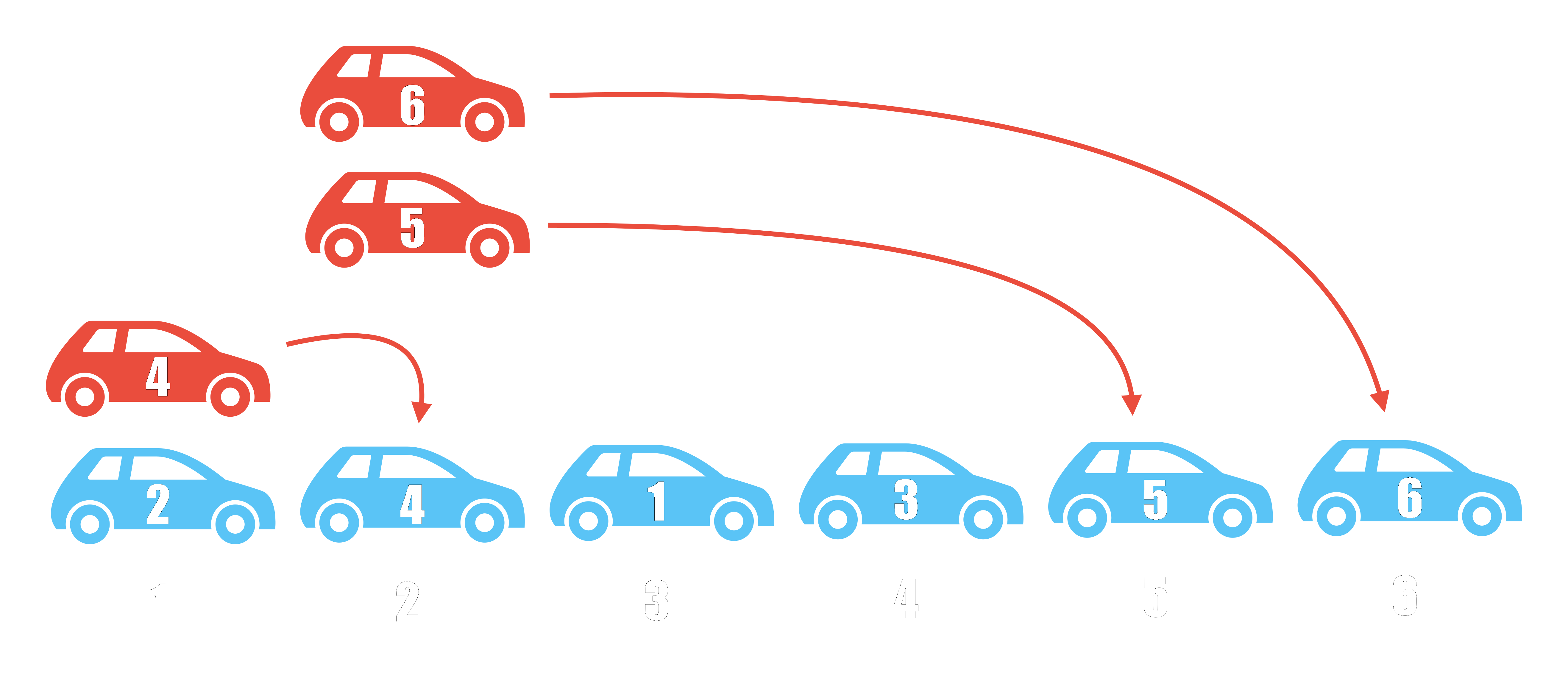

There isn’t much more to the definition of the problem. We have $n$ parking spots labeled in the set $[n] = { 1, 2, \cdots, n}$. Each car $i \in [n]$ declares the spot they’d prefer to park, $p_i \in [n]$. If that site is occupied, they take the next available spot. The cars cannot go back, as it’s a one-way street. If any car leaves without parking, this assignment is not a valid parking function. The figure below illustrates the following parking function of length $n=6$:

\[p = (3,1,4,1,2,2)\]

Parking functions were first defined by Konheim and Weiss (Ref. 1), inspired by problems of efficient information storage and retrieval.

The direct enumeration of the number of parking functions of length $n$ is a super-exponential problem. There are $n^n$ functions $p: [n] \to [n]$. Direct enumeration corresponds to going through all of them and checking if they are parking functions. Checking can be done by running the parking algorithm, as exemplified above, or using an analytical result from Konheim and Weiss: They showed that, given a parking function $p$, and its sorted version $q$, $p$ is a parking function if and only if

\[q_i \leq i, \text{for all $i \in [n]$}.\]From this result, the prime parking functions are defined as

\[q_1 = 1 \ \text{and} \ q_i < i \text{, for all $i \in [n]$, $i > 1$}.\]Another analytical result of this problem is that the number of parking functions is

\[|\mathrm{PF}_n| = (n+1)^{n-1},\]while the number of

This is discussed in Stanley (Ref. 2), exercise 49, p. 98. A simple proof of the number of prime parking functions is also provided in Ref. 3, where I learned about this problem.

With the analytical result in hand, I’d like to talk about an algorithm for the enumeration of prime parking functions that is more efficient than brute force search. The algorithm uses recursion and memoization, and the analytical result will be a guide for the correctness of the solution.

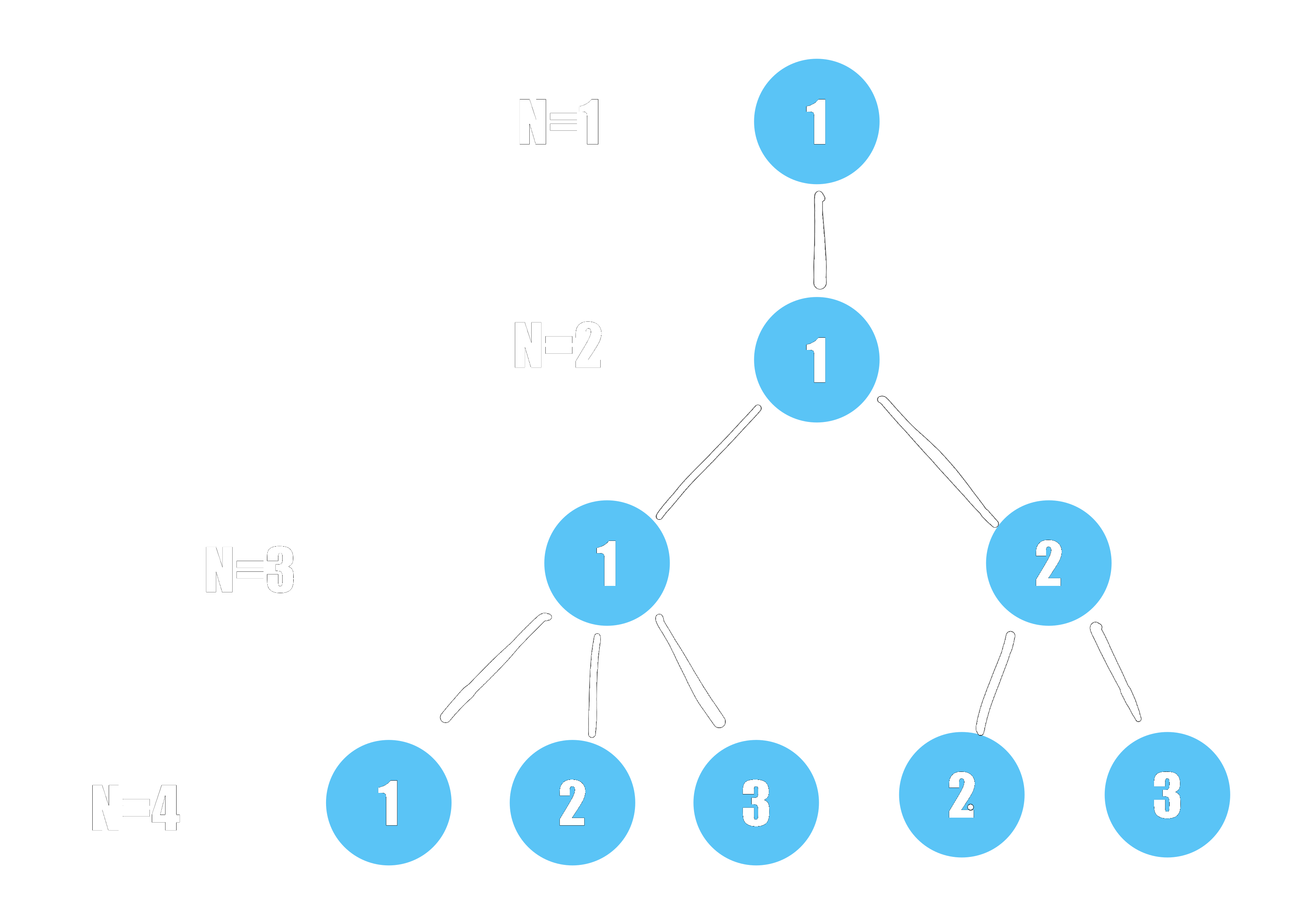

The idea for the efficient algorithm is to build an $n$-ary tree, and with some simple combinatorics, we can enumerate all possible prime parking functions. Below is an illustration of the tree construction process. Starting with $n=1$, there is only one parking function. At $n=2$, there is also one parking function for which $q_2 < 2$. At $n=3$, more options start to appear, and the tree starts branching out, as $q_3$ may be 1 or 2.

In this way, the result of the enumeration at level $n$ is used to build the solution at level $n+1$, simplifying the search. The combinatorial factors involve a few evaluations of the factorial function, which is memoized for efficiency: This means that, instead of recomputing this function every time, every call to the factorial stores the result in a table. Another case where the use of memoization is common is in the evaluation of the Fibonacci sequence.

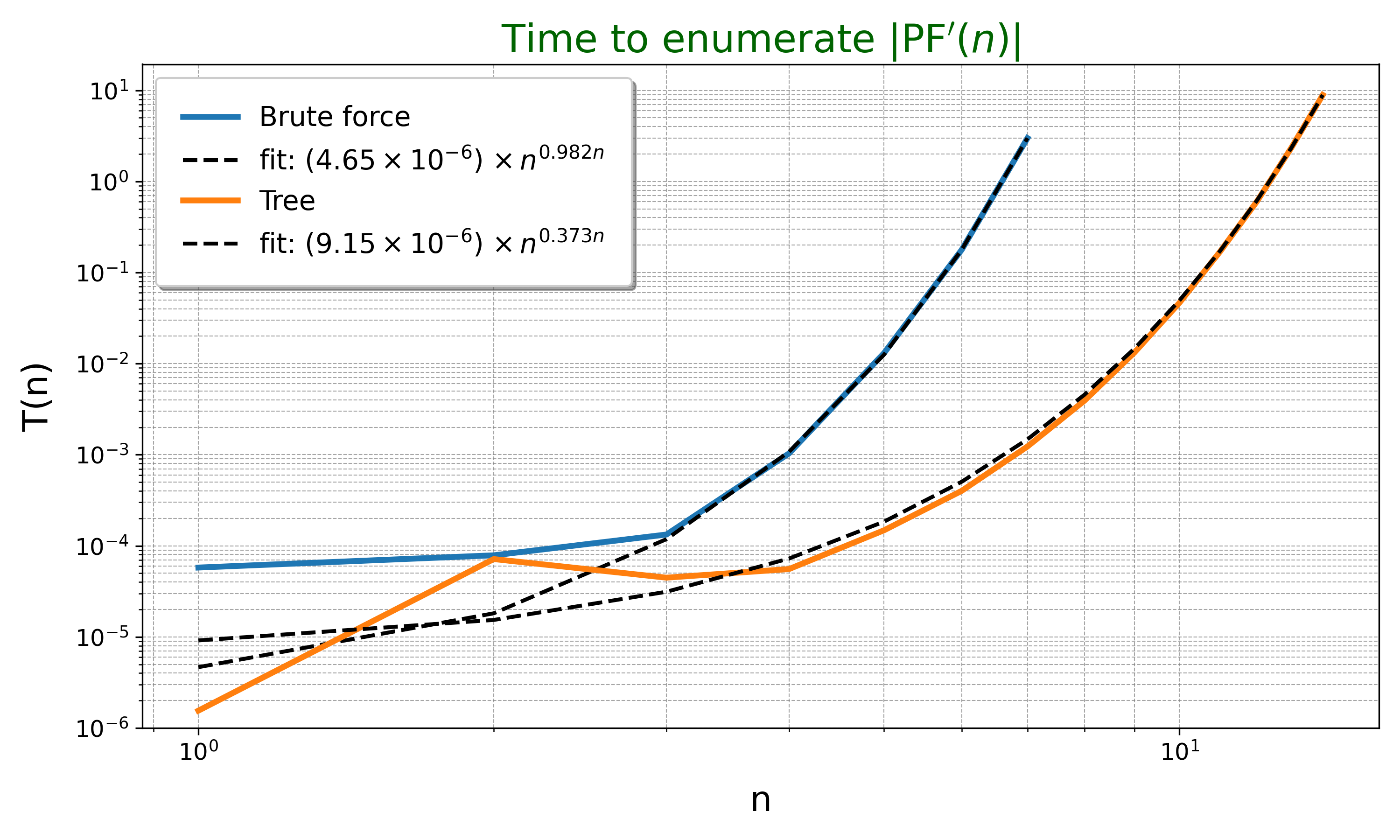

I wrote some code that implements the brute force and the recursive tree enumeration algorithms. Both are compared to the analytical value to verify the result. Below is a plot of the runtime of each algorithm for different sizes of the problem.

The plot also shows a fit of the runtimes. The brute force algorithm is very close to the expected $n^n$. On the other hand, the tree approach follows $n^{0.373 n}$ approximately, which is much more efficient. These are not the same asymptotic growth rate, as shown by

\[\lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{n^n}{n^{0.373 n}} = \infty.\]Another justification for the efficiency of this algorithm is that the number of leaves at level $n$ in the tree is given by the Catalan numbers, which grow only exponentially. This is not the final complexity of the algorithm, however, as the cost of the tree traversal operations is not accounted for.

As an interesting side effect, the recursive tree allows us to efficiently obtain a random sample uniformly from all parking functions of length $n$. This is also done in the code, which is available on Github.

I’ve included some interactive flashcards to this post with the main ideas. The web app for the flashcards is called Orbit, a project by Andy Matuschak. To learn more about spaced repetition, you can check this explanation by Nicky Case.

References

- A. G. Konheim and B. Weiss. An occupancy discipline and applications. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 14 (1966), 1266–1274. doi.org/10.1137/0114101.

- Stanley, R. (2023). Enumerative Combinatorics (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Duarte, R. and Guedes de Oliveira, A. The Number of Prime Parking Functions. Math Intelligencer 46, 222–224 (2024). doi.org/10.1007/s00283-023-10275-5